When designing Wellington houses we are graced with the most amazing and diverse backdrops that provide the ‘challenge-obsessed’ architect with a dare to create an experience befitting the landscape. It’s is also an opportunity to shape every facet of the ‘home’ experience, from street presence to the intimate spaces, under the most complex site conditions. Part of creating this experience is the opportunity to empower those exploring ‘house’ as a place to ‘dwell’.

Architects who have accepted the challenge, and been critiqued by their peers, have been rewarded with New Zealand Architecture Awards by the New Zealand Institute of Architects (NZIA). Given annually, these awards celebrate the most innovative, impressive and considered designs in the region. Below is a sample of some of last year’s winners who have designed and built homes that will stand the test of time.

Like Moller, some architects chose to use a material’s qualities to play a key role in defining spaces. The material selection reflects how their client may want to use the space, how they may want the space to make them feel, or how they want the room to relate to the landscape beyond. The Eastbourne House by Tennent+Brown uses this notion of the ‘considered palette’ to define and emphasise space elegantly. The use of unpretentious cedar and concrete create beautiful, bright interiors that make use of the light to create warm, cosy spaces. The house has outstanding outdoor space and in Wellington we all know this means standing up to the fierce elements of an exposed site. In this instance, this irresistible and compelling shelter can also turn inwards on itself and focus on an enclosed garden.

Another project that takes on a challenging site and makes the most of it is Box Living’s Corrondella project. This small hideaway is perched in a clearing between a stormwater drain and steep bush-clad hills. By adopting a modular box approach, which has become the company’s trademark, the architect has embedded this house into the site. Using changes in levels, small nooks, and courtyards as extensions to space, the house appears larger than its actual footprint. Box Living has fashioned an elegant sequence of rooms that response to site and brief. It is in the focus on simplicity and detail where it matters that Corrondella provides evidence that cost effectiveness need not be the construction of a standardised plan. Through clever design and a rigorous process, bespoke can produce an elegant and sophisticated home on budget. As a result, the site has been maximised and the dwelling designed to give rise to inspiring private views and sun-filled spaces: a warm little bush retreat in which to take respite from urban frenzy.

The bach and associated connotations of relaxation over a beer — or Pinot — have rejuvenated a typology that favours open-plan living and a relationship with the landscape. In the Paraparaumu House, Geoff Fletcher Architects has created an elegantly framed visual link to the exterior via an understated form. This container, another built on a budget, is an addition to a classic Kiwi bach. The sophisticated and unfussy detailing draws the lush bush in, to be absorbed and appreciated from a beautifully sculptured interior. A splash of colour is used sparingly and only to reiterate the framing of the bushscape. To enhance and

From small bach to the large, sweeping spaces of a modern home by Ballara Bulman Chin. Here, the architect uses a working farmhouse to explore the open plan. To suit the needs of the Mangaroa family who live here, the building has few walls and a large atrium over the kitchen, extending the link to the upper floor. Externally, a sheltered courtyard connects to the kitchen/living areas along the building and is a sculptured transition between inside and the landscape beyond.

Sometimes it is the bold use of material and form that gives the architecture its defining characteristics. Here, Kerr Ritchie have subtly manipulated floor levels to organise the open-plan living area, including a strong use of structural form to add detail to both interior and exterior. This house has taken over ten years to realise, and during that process of refinement every element has been perfected to provide stunning spatial qualities, with a careful attention to detail.

In keeping with the idea of home as retreat, John Mills’ Tui House sits snuggly in the bush setting. As the title suggests, it is inspired by the idea of making one’s home within the bush canopy. Atop its domain, this beautifully crafted treehouse is a respite from the hectic city. Large decks reside over sweeping views, engendering a quiet environment within which to relax and also withdraw. Mills’ hallmark use of colour has been conservatively applied as subtle shades of green against rich timbers. The colours reinforce an internal bushscape in stained sheets of ply befitting this exquisite location and considered spatial arrangement.

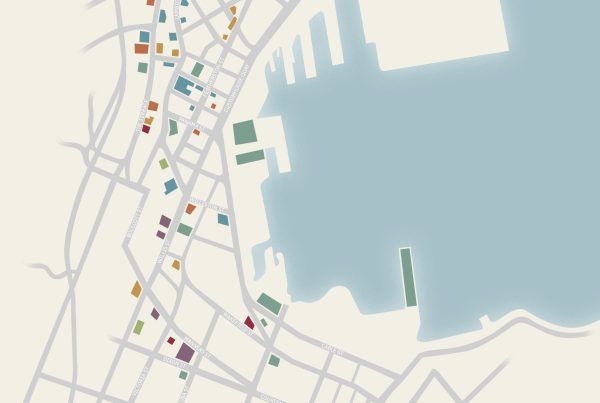

Another project that uses colour and the view beyond, Parsonson Architects’ Seatoun Heights House is a lovely composition linking inside and outside through framed view shafts. Due to the elevation of this site, the owners enjoy expansive views out over the harbour while remaining surprisingly sheltered from prevailing northerly winds. The top level is a large glazed platform, giving rise to a light and warm living space made rich through the extensive use of timber. In contrast, the lower-floor rooms gain warmth through intimacy. The smaller spaces rely on a relationship to landscape through a controlled panorama to give each room space, focus and a distinct identity. Linking both levels is the nucleus, or family room, which is enveloped in green, walls and floors. This delightful play with colour punctuates the transition and literally brings the outside in. It’s gesture questions that line between dwelling, site and interior.

Waking, sleeping, re-creating, loving and living. We spend so much time in our houses that it seems a shame not to make your place of residence both functional and a place of interest. The house designs featured in this article play with many concepts around how to dwell. With both large and small sites, and large and small budgets, the architect’s aim is to project the persona of the client through architectural expression. There’s more to designing a house than just bedrooms and living rooms under a roof. The house has evolved into spaces that symbolise the personal, an exhibition of our tastes, values and even our personalities. It is a place to orientate ourselves, our lives and the lives of others, through careful design that takes into consideration every millimetre. The home can become a respite that refreshes and inspires, preparing us for our increasingly intensive urban lives.

A proverb from the Tales of the Hasidim tells of a tourist who paid a visit to a renowned rabbi, Chofetz Chaim. He was astonished to see that the rabbi’s home was only a simple room filled with books, plus a table and a bench.

“Rabbi,” asked the tourist, “where is your furniture?”

“Where is yours?” replied the rabbi.

“Mine?” asked the tourist, “but I am only passing though.”

“So am I,” said the rabbi.

What is home to you?