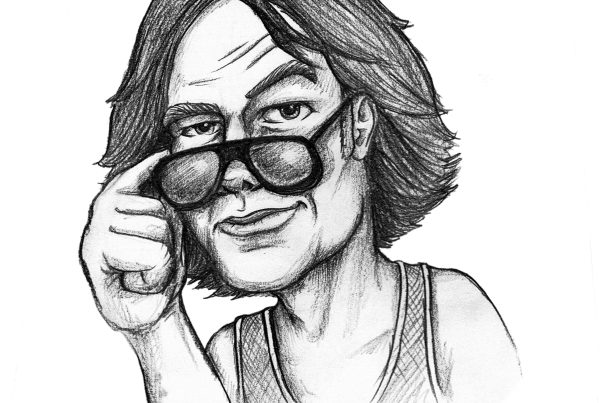

John Edwards, our still newish Privacy Commissioner, sits profoundly and squarely in this latter group. He is a quietly spoken man, soberly dressed in a plain grey suit, white shirt and dark tie, and with the build and demeanour of an ever so slightly pugnacious half-back. He is — in short — exactly the sort of person you might walk past every day in Lambton Quay, who by their outward demeanour could be in charge of the photocopying, or tasked with keeping whole branches of government humming.

“The Buzzcocks changed my life,” he says. Instantly, I am smitten.

Edwards grew up in the Taranaki, mainly. He was a diligent but — in his own words — “unexciting” student, who nonetheless did well enough to be accepted into law school at Victoria University. He says inner-city Wellington life in the mid-1980s suited him just fine. There was good music at a couple of downtown pubs, and a pint of beer was neither a second mortgage nor yet an occasion for craft beer snobbery one-upmanship. And — in the years before the rise of the property developers — inner-city Wellington was still a place where you could find a cheap flat and pretty much have the streets to yourself over the weekend.

Wellington city, its bands and the imported post-punk — The Buzzcocks especially —he could hear on Radio Active every day were enough to nip in the bud Edward’s brief dalliance with adolescent Christianity, and to give him a love for a decent chord and a well-spat lyric that remains to this day.

It’s clear that Edwards enjoyed his student life immensely. But it’s just as clear that he remained a hard worker. We’ve a mutual friend working in his office. Let’s call him ‘Charles‘, since that is his name. We’ve each known Charles for well over 20 years.

“We used to have great conversations on the footpath outside parties,” says Edwards. “I was always just leaving as he was arriving”.

He laughed at that, but I swear he gave a thoughtful little nod as well.

For holiday work — and, all joking aside, this probably says more about our Privacy Commissioner today than the reminiscences about Gisborne Gold and The Gordons ever will — Edwards worked in Mt Cook National Park, building and maintaining tracks.

And I very much like the fact that this ex-law student, occasional habitué of punk gigs at Bar Bodega, denizen of Suzy’s coffee lounge, and now guardian of our legal right to privacy, has also participated in alpine rescues, and has climbed Aoraki/Mt Cook. Twice.

“After graduating, I moved back to New Plymouth for a while, and I got a job with a local law firm there, which seemed like a good step. But most of what I was doing was conveyancing, basically arranging for the movement of big chunks of land. And, well I wasn’t terribly good at numbers for one thing, which made me a bit of a liability with the trust accounting… and it just wasn’t exciting me. It didn’t feel like what I’d got into law for.

“So I applied for a job with the Office of the Ombudsman. Back then, if you made a request under the Official Information Act, and it was denied you, then you could make an appeal to the ombudsman. There were two ombudsmen at that stage, and I was helping them with the reviews, and I found some of that fascinating. I was there for three years, and then the Privacy Act came along, and one of the things the Privacy Act changed was the way in which the Official Information Act was used.

“Previously, your right to access your own information was a part of the Official Information Act, but the new Act carved it out, and put that right into the Privacy Act. And that Act — to all intents and purposes — led to the creation of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner. That gave a proper framework to the protection of citizens’ privacy. Before that, it had been overseen by several different government departments, but having an official Privacy Act, and a Privacy Commissioner, meant that every government department from then on would have set guidelines for what they could and couldn’t access. They couldn’t just sleepwalk into these vast databases.

“So I asked the first Privacy Commissioner if I could give him a hand setting up his office. The idea was that I could offer specialised advice on information law, which is everything to do with freedom of information, intellectual property, all of that… and that seemed to work out pretty well.”

We talk for a while here about the admirable prescience of the Privacy Act. Back in 1992, when the legislation was being drafted, the dangers of information stored digitally — accidentally being revealed to parties who had no legal right to that information — was hardly front-page news. The UN had already warned of the threat to personal privacy posed by new technology. But New Zealand did something slightly different to the rest of the world. Rather than simply write new legislation to cover digital information, we took the opportunity to look at our entire privacy framework, and then set up this new office to oversee the whole sector. We lead the world in this, and our privacy model has been adopted by several other countries.

But as Edwards says, the huge bulk of what the Office of the Privacy Commissioner does is below the surface. By the time there is a complaint to investigate, failures have already occurred. Much of the commission’s work is advising and educating departments and organisations on how never to be the cause of a complaint at all.

“It was a singular moment in our history,” he says. “Quite independently I came across three or four cases of quite hideous abuse. It was a time in the 1990s when a whole cohort of ex-patients had reached a stage where they could rationalise what had happened to them, and they were ready to speak out without some of the shame, and the terrible lack of empowerment that had been with them since the 1970s. I was just a practising lawyer at the time; I had my office in Willis Street. And, well, my brother was one of those ex-patients. He had kept it all bottled up, but by the mid-1990s he was finally ready to talk. I went through his file, and that produced some of the most compelling evidence.”

There’s a pause here, as I take in what Edwards has just told me, and, I guess, as he turns it over in his mind again. He takes a moment, and carries on.

“And by coincidence, I was doing some work for the Department of Corrections, and they had someone who was preparing a file, and another colleague of mine was acting for someone, and then literally dozens of people were coming forward. I started to put it all together and cross-reference stories from people who hadn’t spoken to each other in decades, and there was a remarkable degree of corroboration. I knew then that we were tackling something massive.”

Around this time, Edwards was interviewed by Radio New Zealand, and as a result of that, and other media publicity, the floodgates opened. The original case had been against Lake Alice Hospital, in the Rangitikei, but it would grow to encompass patients from all of New Zealand’s ‘mental institutions’.

Edwards and others compiled a portfolio of cross-referenced cases, some of which stretched back to the 1950s, which was presented to Bill English — the Minister for Health at the time — who, in Edwards’ words, and to English’s eternal credit, said “We’re not going to hide behind legalities on this, this is horrific, and we’re going to act on it.”

About 200 former patients received significant compensation and the Confidential Forum for Former In-Patients of Psychiatric Hospitals was set up, chaired by future Governor General — and an Edwards mentor — Sir Anand Satyanand. After nearly a year of entirely pro bono work, Edwards moved on from the case and returned to his practice. It is a remarkable story, but Edwards tells it briefly, and with absolute modesty.

From that time on, I know that Edwards has charted a spectacular career path; that he has a family; that he lives in Mt Cook (the suburb, not the national park); that he has two children with his partner Sarah; and that his dad wrote the shipping news for the local Taranaki newspaper. I know all of that. But what I’m thinking about, as I take the lift back down to Featherston Street, is that this utterly unassuming man started a process that immeasurably bettered the lives of hundreds of our most vulnerable and desperate citizens.

And he likes The Buzzcocks.