A musician is endlessly youthful, their joy in life will remain unfaded, and they will march on — burning bright to the last, spared the dimming of the twilight years — until they expire with the moment and majesty of a collapsing sun, probably at the hands of a jealous wife or husband, or by slamming their head once too often into the rim of the Rolls-Royce’s steering wheel, as it plunges to the bottom of another hotel swimming pool.

Or, y’know, that’s the myth some of us would like to believe. It’s nonsense, of course. All the professional musicians I know certainly enjoy what they do, and they mostly retain the glorious humour and camaraderie that people who spend their lives working at something they love, with people they respect, always do. But musicians still wrinkle and fade and seize up like the rest of us, with only a few apparent immortals to sustain the legend.

So, I was kind of unprepared for my first glimpse of Rodger Fox. All I knew about Rodger at this point was that he had been around all my life. My Mum and Dad used to drive from Hamilton up to Auckland to see The Rodger Fox Big Band play in the mid-1970s, nearly 40 years ago. Which means I walked into Rodger’s office at the New Zealand School of Music expecting to meet a man of around my Dad’s generation. But, no.

Rodger appears to be in his late 50s at the most (I find out later he is actually 61). He has smooth and unmarked skin, a full head of damnably lustrous hair, a pair of eyes that actually do twinkle, and a laugh and grin quite promiscuous in their willingness to appear suddenly.

In short, alone in all the world, Rodger Fox looks exactly like his own publicity photos.

I was 19 or 20 when I started the Rodger Fox Big Band, he tells me. We were pretty successful from the get-go.

So that explains the age thing. And yet, it explains nothing at all.

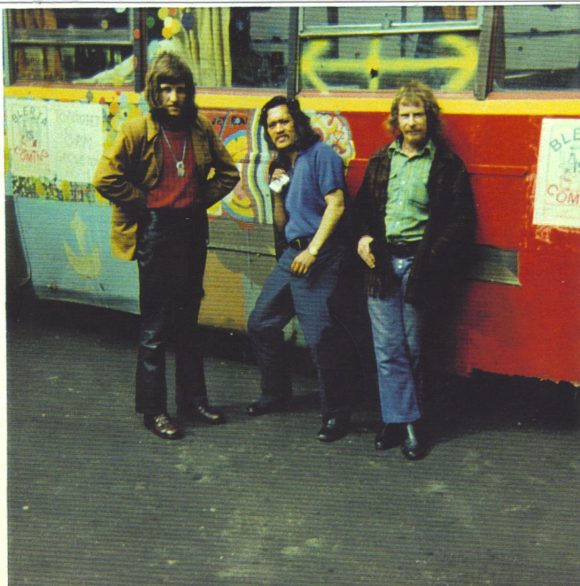

Quincy Conserve in front of the Blerta bus.

Most bands started by 19- or 20-year-olds, even if they go on to success, are grumpy little foursomes of spotty shoegazers. But Rodger pulled together 18 of the country’s best jazz, soul, rock and funk musicians, and melded them into one ferociously well-disciplined ensemble, who then rehearsed and honed their sound until they could genuinely claim to be of international standard. (My Dad was no slouch at his jazz. He grew up playing nothing else, and he sang well enough to appear on the undercard at Soho’s Ronnie Scott’s a couple of times. He always rated The Rodger Fox Band as worth the drive to go and see, and he made a special point of seeing them at the Montreux Jazz Festival when he was there.)

So what I really want to want to know is: how is it that a kid from Mana College had the gumption to do what he has done at all?

I started out trying to learn the violin. My parents were both musicians, my Dad especially — I’ll tell you more about him in a minute — but they had this idea that you shouldn’t teach your own children to play, that it was better to go to a teacher. So I got packed off to the nuns to learn violin.

And, I gotta be honest, violin wasn’t my thing. Basically, I used to affect a case of hiccups. I got quite good at that. Within minutes of the lesson starting, I’d be outside the convent with these spasms racking my body, then I’d duck back in at the end and scratch out a couple of notes. Pretty soon the nuns summoned my parents to a meeting, and told them that young Rodger might not have the makings of a violinist. So my Dad found me a trumpet…

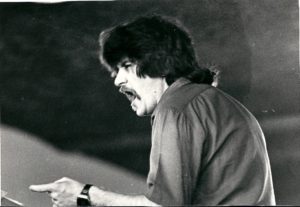

Fox at Mana College in 1981.

My Dad was a violinist himself, and a trumpet player. He was heavily involved in the brass bands, and he became the music director for the New Zealand Army Third Division band. And they were stationed up in the Pacific, with the Americans mainly. So he got exposed to the music the American bands were bringing over, y’know, the jazz and swing that Glenn Miller was playing. So he began to use a lot of that music with the Third Division brass band, and in time he brought a lot of it back to New Zealand. And, you can imagine, it was a very different sound for the New Zealand brass band scene, which were based more on the English colliery bands… it was a revolution. This music was unheard of back here.

So that was the household, one minute you’d have my mother teaching piano, with some kid thumping out Bach, and there’d be Paganini on a violin somewhere, and the next minute there’d be Glenn Miller or Woody Herman on the turntable. It was pretty eclectic.

Dad was conducting and arranging too, and getting a good reputation at it. We went from Invercargill to Gore, but in the 1950s… there wasn’t much there for the family, and, well you know, there wasn’t much going on if you weren’t intending to be a farmer. So he applied for the job of head of music at Mana College. And we moved up here. I was ten.

I went to Mana after a few years. I even had Sam Hunt as my English teacher.

We talk here for a while about Sam. Rodger tells me that Sam was a legend among the students. In his stovepipe black jeans and fringed suede jackets, trying to do his work in an English department staffed by middle-aged men in collars and ties. It’s a brilliant image, but it came at a price. Sam was clashing so badly with his own head of department that he was banished from the building that housed the English classrooms. It was Rodger’s father, who had a spare room in the music building, who gave Sam a place to teach. Rodger goes on to tell me that he also had Ray Henwood as a science teacher, but that is going to have to be a story for another day.

Rodger took to cornet and trumpet, and rose up quickly through the ranks of the school bands. And then, as Rodger tells it:

It was one of those conversations. My Dad came home, it was around Christmas, I was 13, and he says to me, “Have you got your trumpet?” So I ran upstairs and fetched it, and when I got back down he took the trumpet, handed me a trombone, and basically told me I had six weeks to learn it. He’d just found out that all his trombone players had left school, and he needed me to step up. So that was it, that’s how I became a trombone player. Luckily I took to it pretty fast.

Years later, I look back, and I know it’s the best thing that ever happened to me. There’s always ten trumpet players around for every two trombone players, so I was in demand…

I played in the Wellington Youth Orchestra, the local brass band, and then I got into the New Zealand Youth Symphony Orchestra. It was 1967, and the government was keen on apprenticeships, and the symphony orchestra got onto it. They had put together a national trainee orchestra as a training scheme for professional musicians. So I applied for that, and I got accepted. It was a three-year apprenticeship.

But, a couple of weeks later, I get another letter, telling me that there hadn’t been enough retirements from the orchestra, and my apprenticeship basically got cancelled. It was one of those days I guess. Because, that night there’s an ad in the Evening Post, “Brass players wanted”. The band was Quincy Conserve. I was 17 years old.

Quincy Conserve — and there are clips on YouTube to back me up on this — were a red-hot jazz/funk/rock beast. They owed a chunk of their sound to the New York funk supergroup Blood, Sweat and Tears, but they were also a tight, lean, and fantastically entertaining and danceable unit in their own right. Rodger turned up, played one audition, and was on stage that night.

So I called up my Dad, and I said, “You know that classical trombone career I was going to have… well I’ve joined a rock band.” And he said, “As long as you do it the best you can, that’s all we want.” And that was that.

So you had one the biggest gigs in town?

Yeah, I guess so. We were playing four gigs a week at least. We were house band at the Downtown Club, and we were also studio band for EMI. There’s not much out of New Zealand on record between 1970 and 1973 that we weren’t on.

What people forget, is how much more work there was around then. For everyone, but especially musicians. There were three or four bands, all with brass sections, all playing in Wellington half the nights of the week. The bars all stayed open until 11pm, and the clubs would be open until 2am, and there would be a band playing everywhere you went.

One day, I have to do a piece for FishHead on that myth — put around by journalists who clearly never got invited to the good parties — that Wellington was a boring town until the liquor companies took over Courtenay Place in the 1990s.

But for now, there is so much of this story left to tell, and no space left to tell it.

Rodger started the band that still carries his name within three years of joining the Quincy Conserve. Realising there was a gap for a dedicated jazz session band, he pulled together a group, and had them in paying work within three months.

In the 40 years since, The Rodger Fox Big Band has played all over the world, and earned good reviews wherever they have gone. Louis Bellson, Joe Williams and Michael Brecker have all performed with them.

Rodger still runs the band, and keeps the average age of the roster at around the mid-20s. Today they sound better and more skilled than ever.

Rodger is also a senior lecturer at the New Zealand School of Music, and leads the school’s highly regarded jazz ensembles. He’s had more influence on Wellington’s music scene than almost anyone else I could name. And yet, all of that might have to wait for another piece, another month. As with all good Wellington stories, this one is still being written.