One thing that seems positive from most angles though, is the business of international education. Boosting the individual student, the school, the local community, the wider region and the country as a whole, the programmes operating in New Zealand today undoubtedly open cultural doorways and add value to the local and national economy.

In Wellington alone, international education contributed approximately $193 million to the economy last year, with more than 5,500 international students studying, and around 100 different countries represented.

A study commissioned by Education New Zealand into the economic value of international education to New Zealand during 2012 found that the total economic ‘value-add’ from enrolments of international fee-paying students in our schools was around $361 million, $310 million for secondary schools and $51 million for primary schools. This was a not insignificant 14 percent of the $2.6 billion total value for that year. In the first half of 2014, the number of international students in Wellington increased by a percent, aligning with an upward swing across the country as a whole.

Grow Wellington is the economic development agency working to accelerate growth in the region, with the mission of making us more internationally competitive. Focusing on exports, they are heavily involved with international education programme promotion, terming it “export education”.

Collaborating with Education Wellington International (EWI), a network of education providers in the Wellington region that host international students, Grow Wellington also links up with other economic development agencies, regional educational groups and Education New Zealand to promote Wellington education products around the world, says Wellington mayoral senior communications adviser, Phil Reed.

EWI and Wellington City Council’s successful Mayoral International Student Welcome at Te Papa in March was a good example of the positive growth in the capital’s export education market, with more than 500 international students in attendance.

“There are [now] almost 7,000 international students in Wellington and they contribute significantly to the local economy,” says Reed. “They also make a valuable social and cultural contribution.”

He says Kāpiti markets mainly on its own, at a series of education fairs, through education agents, parents and ‘sister’ schools with whom they have developed relationships through hosting previous students.

“Our philosophy is to internationalise Kāpiti College and make it a high school that students from many countries would love to come to, to develop their education and their English,” he says. “The gains Kāpiti students can make for this cultural exchange are priceless for all.”

Price though, is something that does come into the equation, with Kāpiti listing fees on its website of almost $11,000 per year for study, $250 per week homestay fees and other costs of more than $3,000, excluding flights, any spending money or extra-curricular activities for the student. This is not even the most expensive programme out there. It seems a new Zealand education may not be accessible to everyone.

Burt says there’s no doubt that the college is involved in international education partially for profit, but that this money is destined to be channelled back to both Kiwi and foreign students.

“The New Zealand government is keen for Kiwi schools to have a steady revenue stream that can be poured back into resources,” he says. “Many of the kids’ parents also come out and spend tourism money while delivering or picking up their children.”

With their programme running successfully, and proving financially viable, Kāpiti College has started a new concept within its international education programme, running a specialised international class mixing the students from overseas with Kiwi students at the college. Burt says another teacher came up with the idea after taking a group of New Zealand students to stay in Bangkok, at one of the college’s partner schools.

“He proposed having a class of Kiwi kids in Year 10 who would learn about social studies and English, with a focus on the rest of the world,” he explains. “They would begin to learn Mandarin and Thai, and international students would be added to the class as they arrived during the year. The Kiwi kids had to apply to get in after a parent information evening, and [they] would be offered first rights to go on a trip to Thailand or to China in November. So far everything is going better than could be hoped for and the class is developing a wonderful learning culture.”

According to Burt, as well as focusing on cultures from other countries Kāpiti’s international department offers the opportunity to experience Māori culture, enriching that aspect of the school’s identity.

“The school marae hosts pōwhiri for all visitors and new students,” he says. “Recently, there were pōwhiri for 150 Japanese students from Tokai Urayasu High School in Tokyo, who came for two days, and we are presently hosting 16 students from Bangkok, who also were given a pōwhiri. This mixing of the cultures is another important aspect of the programme.”

Several international students currently enrolled at Kāpiti have found the experience so valuable that they have plans to remain in New Zealand until they reach tertiary education.

Zi Goh is 17 and comes from Singapore. She is in her third year of study at Kāpiti, and plans to stay through to university. Originally shy and quiet, Zi says she has opened up socially, and is now the college’s head international student, helping organise events and activities, and acting as mentor to younger or newly arrived students finding their feet. She says the biggest challenge she has come across is a change of host family a while back.

“There weren’t major problems [with the first homestay] but I feel like I fit better now,” she says. “I just didn’t bond quite so well the first time.”

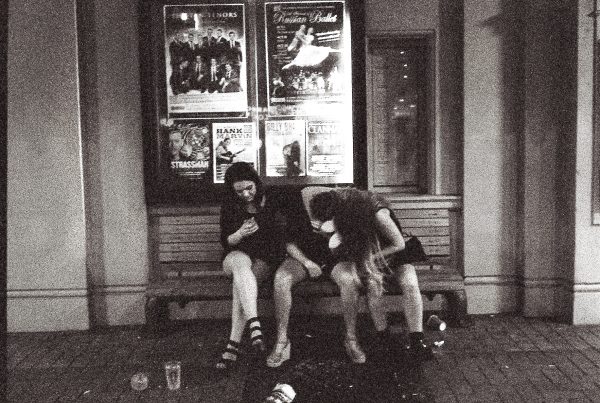

Ryo Maeda, from Japan, also had a change of homestay family, but is grateful for all his experiences in New Zealand, identifying strongly with his Kiwi friends, and speaking English fluently with a Kiwi twang and plenty of colloquialisms thrown in, despite arriving knowing only how to say one-word basics such as yes and no. Cheeky and sociable Ryo says he’s had no problems bonding, and takes every opportunity he can to hang out with both his Kiwi and international student mates, particularly if there are any pretty girls around, illustrating that being 17 has its similar traits wherever you come from in the world.

“It was easier than I thought [to come to New Zealand],” he says. “I felt well adapted, and I want to stay until university so I can become a pilot, which is something I could not do in South Korea.”

Burt says many of the college’s current students look set to follow in the footsteps of their other international graduates, who have gone on to achieve in many different areas. These include a Chinese student who arrived in Year 10 with her mother in tow as she was so young, who has now completed a teaching degree; a Vietnamese boy who went on to gain an engineering degree at Canterbury and returned to work for his father’s engineering firm in Vietnam; a Japanese girl who made the National Youth Orchestra; and a Japanese boy who represented his New Zealand Basketball Academy’s team in Las Vegas.

With so many positive stories to tell, the experiences of students coming to New Zealand to study indicate the quality of the international programmes being run at schools such as Kāpiti, and others across the country.

With the economic benefits taken into consideration as much as the social and cultural ones, going both ways, it makes sense for there to be top-level support for international education in New Zealand schools, building stronger relationships with education providers in other countries, and partnership agencies here.

Hopefully, the flow-on effect will be the further opening up of opportunities for Kiwi kids in overseas study. Maybe, the more we are willing to offer international education programmes here, the more they will be offered to Kiwi students in other countries and schools, so that any student, regardless of decile or financial means, can have the chance to broaden their horizons.