“So I feel there is a big onus on property developers to do it right,” he continues, “or to get out of the business.”

Willis Bond, The Wellington Company, the Chow brothers, Precinct Properties, Primeproperty Group and Mark Dunajtschik represent the major property heavyweights in Wellington. Are they ‘doing it right’? According to The Wellington Company director and Property Council president Ian Cassels, New Zealand’s “chronic attitude to property developers” sees them “held in a similar regard to pirates”. McGuinness sheds some light on this with his assertion that “Compared with other professions, developers tend to be more individual in their output… historically in New Zealand [they] have tended to do their own thing.”

US sociologist David Harvey’s essay ‘The Right to the City’ presents an interesting counterpoint to this statement. “The question of what kind of city we want,” states Harvey, “cannot be divorced from that of what kind of social ties, relationship to nature, lifestyles, technologies and aesthetic values we desire. The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right.”

The notion of common rights is enough to make any developer shudder — or anyone who shares their interests, like former mayor Kerry Prendergast, who has characterised the community voice as “schizophrenic”. Property lawyer Stephen Franks shares this view, stating that “Developers shape all vibrant cities. Planners and consensus processes often produce sterile spaces, with what people think (and say) they want. Successful developers often have a better idea of what they actually prefer, and make the trade-offs between wishes and what can be afforded… with super-profits for the successful, and failure, this weeding fork is the way dynamic cities evolve.”

Bond, Willis Bond

Two of the evidently hardier ‘weeds’ in Wellington’s property terrain and developer network are The Wellington Company and Willis Bond, having both left their mark through numerous game-changing projects in partnership with the council.

“Our history demonstrates three fairly brave public thoroughfare projects,” says The Wellington Company’s Cassels: “Umbrella Park [from Cuba through Cornhill to Victoria], Leeds/Eva through the bottom of Hannahs, and Left Bank — connecting Victoria to Cuba. These were all undertaken with limited resource and low return, but will all be extremely valuable to the long-term intensification of Wellington.” On Willis Street, The Wellington Company’s Conservation House and Telecom building “are major contributors to the city’s green building stock,” says Cassels — Wellington’s top-rated buildings for energy being Meridian Energy’s head office on

The Wellington Company is currently working on an invigoration of neglected coastal gem Shelly Bay, although they normally specialise in office buildings. The company was established in 1990 with the purchase and occupation of Invincible House in Willis Street: “The 1980s had seen a glut of commercial office buildings constructed, and by 1990 the property bust had well and truly arrived with many commercial buildings selling at a quarter of their 1987 peak,” remembers Cassels. “We were particularly attracted to the value that residential brought to the city and the huge amount of sense that ‘living in the city’ made.”

Willis Bond, a company much loved by the city council, are attracted to the same principle — and also born in 1990, with McGuinness’s purchase and transformation of the old Clarendon Tavern on Taranaki Street into Molly Malone’s pub. They have since focused on mixed-use, high-end residential buildings: Chews and One Market lanes are also their work, alongside a big chunk of our waterfront. Queens Wharf, St Johns, Mac’s Brewery, the NZX, Clyde Quay apartments and now Site 9 and Site 10 are all Willis Bond babies.

The company won the Clyde Quay contract after Wellington Waterfront put the old Overseas Passenger Terminal site out to tender in 2005. It was then the biggest non-government development project in the country, and was passionately protested and appealed by Waterfront Watch. One-and-a-half years at the Environment Court and the global financial crisis delayed commencement of construction by LT McGuinness — Mark McGuinness’s construction company of choice — to 2012. The current building, now almost complete, is worth almost $180 million, 71 of its 76 apartments selling for between $1.3 million and $6 million a pop. Willis Bond owns all the commercial tenancies on the ground floor.

Earlier this year, the company got the green light for another ambitious waterfront complex on Site 10 — the former Shed 17 location — despite initial submissions to council numbering 97 for and 99 against the designs. The Environment Court rejected initial plans, responding to submissions with a ruling that the building’s height should not exceed 22 metres. Current plans are for a 25.7‑metre building, but as a consolation, the contentious upper (sixth) storey has been allocated for public usage. The complex is due for completion in 2017.

At the same time, Willis Bond will be erecting apartments on top of Farmers as part of their Cuba/Dixon Street corner project, which measures 8,000 square metres, twice the size of Chews Lane. Confirmed new occupants WelTec and Whitireia polytechnics, “will certainly help rejuvenate that part of town,” says McGuinness.

“It’s a wonderful opportunity to redevelop that part of Cuba,” he adds, “but the challenge is not to lose the essence of what makes Cuba Street special. It’s got a little grit, it’s got a little bit of a quirk, it’s just a colourful, characterful part of town that is on a human scale and there is a lot of character, both in terms of the people and the buildings.

“How do you deal with the fact that all those buildings on the site need to come down, other than perhaps the facades so you keep the older look, but at the same time keep it small and on a human scale?” McGuinness asks. The incorporation of lower buildings and a lane are two solutions, “and really just mixing up the uses so that there’s something for everyone”.

Bickering bedfellows

Cassels dreams of a Wellington with a super-city council that’s a “dream to work with” — but considering that developer agendas and public interest often clash, especially when it comes to building features like height, anchor tenants, usage and advertising billboards, should it be that easy? Should the council roll over in front of every developer-director with deep pockets and a six-storey blueprint with ‘active edges’ promising ‘economic growth’?

According to councillor Andy Foster, “While a lot of people don’t like the word ‘developer’… somebody has to take the risk, put the money together, the team, the designs… developers play a critical part in creating the city that we use.

“If we didn’t have developers,” he adds, “we’d all be standing out in a field.” Foster is enthusiastic about current council financial support of Mark Dunajtschik’s convention centre opposite Te Papa, which will also boast a five-star luxury Hilton hotel.

Though on the developer end of the deal, lawyer Stephen Franks says working with the council “can involve stupid and opinionated people who have none of their own money at risk, getting a chance to impose preferences that are expensive and add no value, but which developers have to go along with. Much of the heritage worship has that element. People who fear the future cling to the status quo, so our best architects and developers are confined and forced to do dreary conventional stuff.”

So should the council and developers be collaborating? While Foster says, “Absolutely,” Michael Macaulay, associate professor in Victoria University’s School of Government, cautions that “in general most people would agree that collaboration and partnership working are good ideas. Not only because they tend to be better value for money, but simply because they can be more progressive and creative in their approaches. The key element, though, is that collaborations must take into account a sufficient range of views or else the danger is that collaboration can slip into cartel.”

More moguls

There are, of course, more — and some would say better — ways to capitalise on property than to develop. Property heavyweight and shit-stirrer extraordinaire Sir Bob Jones famously abhors the risk of development, preferring to buy, pamper anchor tenants, and then kick back with a cigar as their rents increase whilst shooting the breeze about the rights of landlords, the wonders of paving and why women shouldn’t drive.

Jones formed RJ Holdings in 1961, making his way up the ‘property ladder’ as earthquake demolition and market deregulation created a Wellington property boom in the 1980s. RJ Holdings is now not only New Zealand’s largest private CBD office building owner, but also one of our biggest private corporations, with assets in excess of $1 billion and a portfolio of more than 23 buildings.

Auckland-based Precinct Properties has a sizeable office portfolio too, as the self-proclaimed “largest owners of premium inner-city business space in Auckland and Wellington”. The NZX-listed company has 7,800 shareholders and $1.64 billion in assets, including a great deal of The Terrace: the Ministry of Health building, Pastoral House, Mayfair House, and Capital on the Quay at number 125.

Primeproperty Group’s investments are also widespread, with some properties in Hamilton and Coromandel, though most are in Wellington city, with a number also on The Terrace. The group limit neither their geographic nor real-estate interests, which purportedly extend to a particular enthusiasm for selling billboard advertising on their building exteriors. They own and operate numerous car parks, residential sites, housing estates and hotels, including Abel Tasman Hotel, Central City Apartment Hotel and the historic St George, presumably outbidding Chow Group when the latter was up for grabs.

National Business Review rich listees John and Michael Chow, after whom Courtenay Place’s famous J&M’s takeout is named, have similarly wide, though perhaps more strategically integrated, interests — and more than $2 billion worth of real estate and chicken-salted fries under their belts. They own 70 percent of Wellington’s sex trade, including Mermaids, Il Bordello and Splash Club, with a purported 100 sex workers on their books. This doesn’t stop Kerry Prendergast from hailing them “Great Wellingtonians” who contribute to the economy whilst “giving back to the community” through Exodus gym and their sponsorship of Team Wellington, Saints, Firebirds and Round the Bays.

The brothers envisage controlling a $1 billion empire within a decade, expanding on a portfolio that already includes the Westpac building on Lambton Quay, Vivian Street’s Brendan Motors, Whitireia Polytech, hotel accommodation, Tory Street’s Exodus gym and surrounding retail complex (minus one previously protected kōwhai tree), and a planned 15-storey hotel and brothel complex on the Palace Hotel site opposite Auckland’s SkyCity Casino. They also own a Willis Street complex including Wilson Parking, La’ Shika Bridal, and the Capital Market food court recently launched with the aid of deputy mayor Justin Lester.

Another well-known family investment team are the Papageorgious, who leased the former Espressoholic café site until it was booted out of Courtenay Place. At time of writing, the Papageorgious’ entire $20 million portfolio is up for grabs, and includes a number of heritage buildings on Courtenay Place, as well as Cuba, Tory and Oriental Parade. There has been speculation about their incapacity to redevelop risky purchases or meet earthquake-strengthening costs — but perhaps the liquidation of this larger family trust simply testifies to the particular effectiveness of the more singular patriarchal model of other developers and investors.

“If you put 1 and 1 and 1 together, you actually make 4,” says Andy Foster, discussing how value is generated in urban contexts through collaboration, particularly between council and developers, and through proximity. “You get some benefits of people working together and bumping into each other in the street, and having some of those social and economic transactions that add value,” he says.

“People spark off each other. Put a whole lot of people together, there’s a cross-fertilisation of ideas,” he continues. “That’s why we have cities: you have transactions that are not just of goods and services, but ideas. That’s what cities are about.”

Wellingtonians make this a city of talent, he seems to suggest, just by living and working here together. We just happen to depend on a bit of proactive megalomania to build the stage on which all our talent-sharing fizz-pop becomes possible.

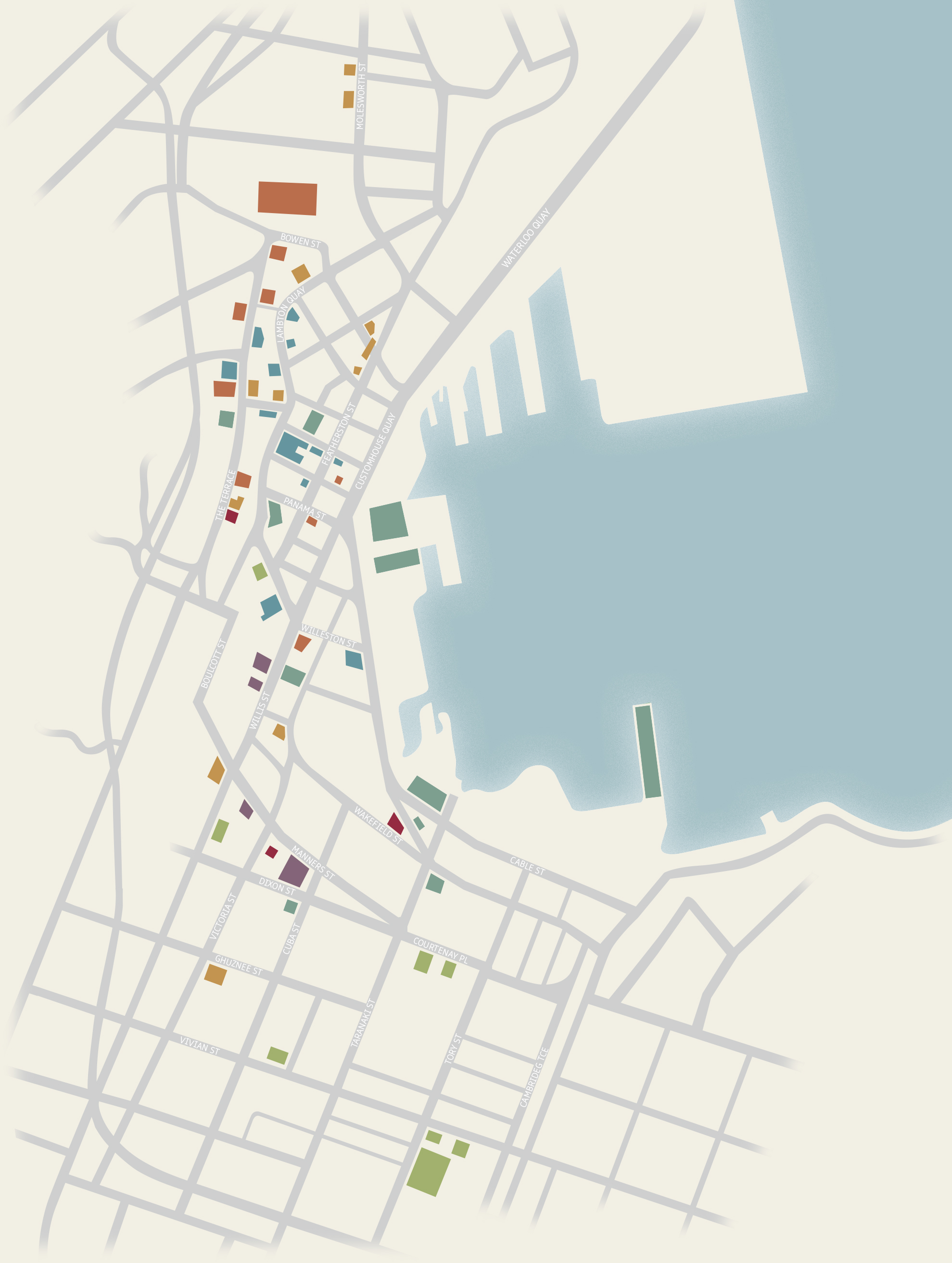

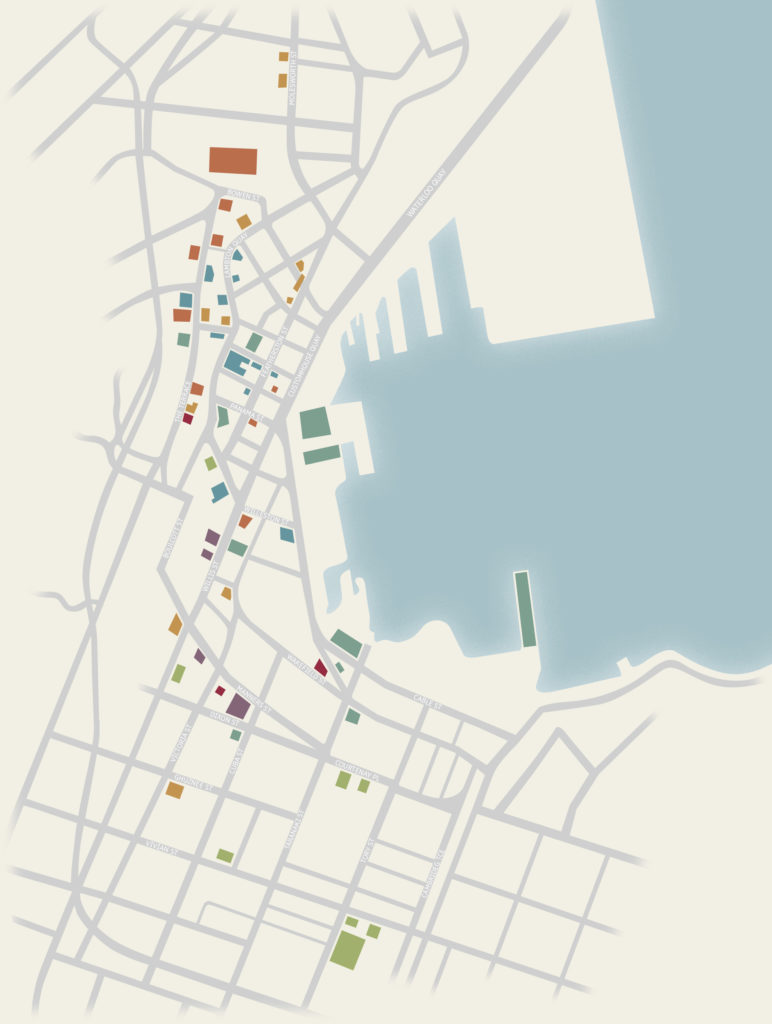

Willis Bond began their work in Wellington with Molly Malone’s. They have recently completed Clyde Quay wharf, and are responsible for the Queens Wharf, Wellington Brewing Company, NZX, Free Ambulance Building and Xero House waterfront developments, with One Market Lane under construction, Site 10 recently signed off and their Cuba/Dixon project also in the works. Chews Lane, Transpower House on The Terrace and Grant Thornton House on Lambton Quay are also Willis Bond’s.

The Wellington Company’s current major project is Shelly Bay. They also own Telecom Central, Conservation House and ASB Bank House.

Chow Group own and run the CMC building on Courtenay Place, as well as Mermaids. On Vivian Street they own Whitireia Performance Centre, Brendan Motors, Il Bordello and Vivian Street accommodation. Chow own Exodus gym and the surrounding real estate on 131–139 and 147–161 Tory Street. They have recently opened the Capital Market on Willis Street next to their Wilson Parking lot and La’ Shika Bridal. The Westpac building is also owned by them.

Mark Dunajtschik has been responsible for a number of large developments in Wellington. The most significant are Asteron Centre, principally occupied by IRD at the Railway Station end of Featherston Street, and the HSBC Building, which is predominately occupied by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. He also owns the quake-prone Harcourts Building, despite trying to fob it off to the Historic Places Trust for $1, and is working with council on the convention centre.

Precinct Properties are Auckland-based and own multiple sites on The Terrace, including 1–3 (Treasury), Pastoral House and Mayfair House, 44–52, 80 and 125 The Terrace. Deloitte House on Brandon Street, 171 Featherston Street, Bowen Campus, the State Insurance Tower, and Central on Midland Park are also Precinct’s.

Primeproperty Group own at least 16 office buildings in Wellington’s CBD, as well as operating hotels, apartments and car parks. On The Terrace, they own numbers 39, 120 and 139. They also own various buildings on Woodward Street (2), Featherston Street, Molesworth Street (55–61), Willis Street (124 and Abel Tasman Hotel), Lambton Quay (86–90), 85–87 Ghuznee Street and Victoria Street (86 and Central City Apartment Hotel).

Bob Jones owns Kirkcaldie & Stains and the surrounding Bayleys and RESIMAC buildings, as well as Lambton Quay sites Legal House, Public Trust Building, Lambton House, Woodward House and number 342. Pencarrow House on Jervois Quay, Solnet and 73 The Terrace, and Featherston House, City Chambers and Wellington Chambers on Featherston Street also belong to RJ Holdings.

Maurice Clark has undertaken much redevelopment, including the former Defence House in Stout Street, the Tower Building on Customhouse Quay and a couple of conversions from office buildings to student accommodation.

Kiwi Income Property Trust own The Majestic Centre, 44 The Terrace and the adjacent 56 The Terrace, which is about to be redeveloped for the Ministry of Social Development.

Argosy own the DIA Building on the corner of Lambton Quay and Waring Taylor Street, Stewart Dawson’s Corner, NZ Post House, the Defence Building in Stout Street (recently purchased from Maurice Clarke) and 8 Willis Street.

Oyster Property Group owns the Fujitsu Tower, Eagle Technology House and the currently out-of-action James Smith Carpark.[/info]

Who should fund earthquake strengthening?

Mark Dunajtschik, owner of the Asteron Centre and currently collaborating with council on a convention centre complete with a luxury five-star Hilton hotel opposite Te Papa, tried to demolish Wellington’s 85-year-old Harcourts Building. After being ordered to bring it up to code, he offered the building and associated costs to the Historic Places Trust for $1.

Bob Jones, too, famously thinks that earthquake strengthening should be funded by government. “Now morally if they change their minds they should pay for it,” he told The Nation. “That happens every six to eight years, and now they’re going to do that again but they don’t pay for it, they don’t offer interest free loans, they don’t even allow us to deduct that cost”.

Willis Bond director Mark McGuinness takes a different view. “Most of the buildings that are yellow-stickered now were [known] earthquake risks 25 years ago,” he says. “A lot of people bought buildings knowing that they’re earthquake risks. So to then ask central government or the local government for money to help strengthen them, it’s almost creating moral havoc in my view. You buy a run-down house in the suburbs and then turn around to central government and say, ‘Can you give me some money to help fix it up?’ That doesn’t feel very fair to me.” Financial assistance should only be given in exceptional cases, he says.

“If you own property that needs updating, it isn’t news, and you’ve got to accept responsibility for doing that work. If you’re not willing to do it, you should sell it to someone who will.”