Jeremy Commons used to put on drawing-room operas. He doesn’t now, but for 14 years he ensured that these intimate dramas were regularly re-enacted, for a small audience of the discerning, at the James Cook Hotel and the Wellesley Club.

Rehearsals took place in his house on Hawker Street, in the shadow of St Gerard’s monastery. And what a house it is! Two-storeyed, high-ceilinged, it was a house of grand pianos and chiming clocks, its walls lined with art of every kind, its surfaces overflowing with books and sheet music.

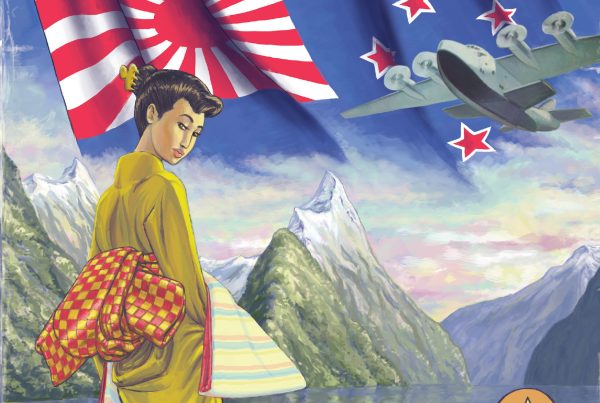

Commons was a lecturer in English literature at Victoria University, but opera was his real passion, right from the age of 13, when he played Yum-Yum in the Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera The Mikado. “To begin with, I thought the love of my life was going to be Verdi,” he says, sitting at his living-room table, various of his academic publications strewn across its top. “I saw a film of La Traviata at 15. But then, a year later, I heard a very famous old recording of [the Donizetti opera] Lucia di Lammermoor… I suddenly thought, as much as I love Verdi, I think I understand Donizetti better. I can see what he is doing, and what he is doing appeals to me immensely.”

At Auckland University, he “frittered away an enormous amount of my time” collecting notes on every Donizetti opera. After that came Oxford University, then an Italian government bursary, which he used for a year of “peregrinations” around the country, studying Donizetti’s manuscripts. It’s an apt word, peregrination, for there is something — in the best possible way — sharp-eyed and falcon-like about Commons. He says of his late and much-beloved partner David Carson-Parker (himself a notable arts supporter), that “he never put anything out without my approving it”, and he deliberately spells out for me the names of opera composers, so as to ensure no mistakes.

Much of Commons’ life has been devoted to unearthing little-known or forgotten 19th-century operas written by men with names like Balducci and Pacini. He has spent countless hours sleuthing in obscure Italian museums and archives. He also once published a collection of every review of every premiere of Donizetti’s operas. “Reviews of that period are as extensive as sports commentary these days,” he says, with an air of regret for opera’s decline.

All this activity has led to “what I regard as a rather undeserved international reputation”, Commons says, in his well-rounded British accent. It also brings the odd conflict of the kind that the classical world relishes: Commons uses ‘Vaccaj’, not ‘Vaccai’, as the spelling of the largely forgotten Italian composer, “as he always signed his name with a ‘j’. Which brings me into conflict with [the opera dictionary] Grove… but I stick to my guns!”

Hearing forgotten opera brought back to life is, for Commons, tremendously exciting. Take Vaccaj’s La Sposa di Messina, which had “the most disastrous performance” at its premiere in 1839, despite dealing with — racily enough — sibling incest. “It was hardly heard by the audience, it was booed so hard. But when you hear the music, it’s a marvellous opera.”

Commons is still active in the arts, financially supporting one young male dancer, among other things. But he is now “trying to draw in my horns a bit”, and, after a health scare, no longer goes out at night if he can help it. When I arrived to interview him, he said, pleasantly enough, “You’ve come several years too late!” This wasn’t true. But he has stopped running his private record label Sirius, named after the Dog Star, which was thought to cause fevers and plagues and drive people mad: “I thought, I may as well have a private joke with myself, that this was an enterprise of madness.”

Nor does he still mount his drawing-room operas. But people like Eastbourne’s Rhona Fraser, who puts on an opera in her garden every year, keep the spirit alive. “In so far as I have a successor here,” Commons says, musing on the idea, “it’s Rhona.”