Whether they had been called names or been hurt by other students were two of the six questions that the 2012 Trends in International Science and Mathematics Study (TIMMS) used to assess bullying being experienced by primary school students around the world. New Zealand’s bullying rates were starkly exposed in this study, which concluded that we have the fifth-highest reported bullying rates among primary school children worldwide.

Bullying is often seen as name-calling and playground fights, but it can be much more than that. So do we really have a clear understanding of what bullying is? Dan Olweus, from Clemson University in South Carolina, has defined bullying as recurrent and harmful acts that involve an imbalance in power. This can range from teasing based on someone’s physical appearance, to throwing tree bark or a punch. Olweus is the founding father of bullying research and intervention after approximately 40 years of working in the field all over the world.

Bullying is not new. Our grandparents received wedgies and had to dodge spitballs. And now our children are being bullied — both at school, where the hallways can at times be a battleground, and at home, where their mobile phones and computers are being used as weapons against them.

In 2013, Vanessa Green from Victoria University’s School of Educational Psychology and Pedagogy (with students Susan Harcourt, Loreto Mattioni and Tessa Prior) produced the Bullying in New Zealand Schools report. Green and her team found that 94 percent of the surveyed schools say they have a problem with bullying.

“This report shows just how much of a problem bullying is in New Zealand,” says Green. “While some New Zealanders may think that we do not have a bullying problem, this is not what our children and our schools are saying.”

Technology has allowed bullying to become even easier and it no longer stops at the school gates. Children enter the boundless and uninterrupted world of the Internet, where bullies can hide behind their avatars and feel powerful from the safety of their mobile phones.

This was shown in Green’s report, which indicated that cyberbullying is a hidden form of bullying, and 55 percent of respondents reporting that it had not been brought to their attention in the previous four weeks. “The bullying can be happening in such a public way, but it is still private in that the adults directly involved with the children can have no idea,” Green says.

Bullying and cyberbullying are often put into separate categories, but there is a huge overlap, says Green. Children that are being cyberbullied are often also being bullied in a traditional way.

Green argues that the TIMMS statistics indicate that bullying is a major issue in New Zealand that must be addressed. We make our children go to school, she says, and it is their fundamental human right to feel safe and secure while they are there. Yet we are not ensuring that their environment is safe.

Chief Humans Rights Commissioner David Rutherford says that we need to be kind and brave, and that we need to stand up to human rights abuse right in front of us.

“It is a disgrace that we do not have good data,” he says. “We do not know exactly what the numbers are, but we know we have a problem.” He says that to reduce New Zealand’s bullying statistics we need to stand up for others and work together to help.

“The thing that people who have been bullied remember most, that harms them most, is that nobody stood up for them. So e tū, stand up. Do not be a bystander,” he says. Rutherford says that principals who know what they are doing acknowledge the issue and are working to reduce bullying in their schools. “We realise that it is the leadership of board, principals, teachers and students that will make the difference.”

Jenny Williams, principal of Samuel Marsden Collegiate School, says bullying is something that exists, to some extent, in all schools. “I have been teaching a long time, and I believe that it is an inherent problem. It is part of human nature, because we worry about people that are different.”

Like Green, Williams is quick to identify New Zealand’s hesitancy to face up to bullying. “It is an issue in New Zealand because it is hidden. People do not want to talk about it”, she says, “and the first step to solving any problem is accepting that it exists.”

The next step, of course, is to take action. Victoria University’s Accent Learning has taken an active role in this, and they believe that they may have found a way to prevent and intervene in New Zealand’s bullying problem. Their answer comes in the form of an anti-bullying programme called KiVa, which originated in Finland and is short for kiusaamista vastaan, meaning ‘against bullying’. This programme aims to change the behaviour of students by encouraging them to take control of their own schooling environment, and to stand up and speak out if bullying occurs. The programme has received numerous international awards, such as the 2009 European Crime Prevention Award and a 2012 Social Policy Award in Vancouver, Canada.

After more than a decade, Finland is continuing to reap the rewards of KiVa, demonstrated by a reduction in their high school bullying statistics. The programme’s success elsewhere has also been enormous, with reported reductions in both self- and peer-reported bullying and victimisation. In fact, 98 percent of students involved in discussions with KiVa teams feel that their situation improved.

KiVa is the first programme of its kind to be introduced in the southern hemisphere. It focuses on prevention, intervention and monitoring, with one overall goal: to reduce bullying. It is currently designed for students in Years 2–Year 8, but a unit for junior secondary schools is currently being translated.

Deidre Vercauteren, the education programme manager at Accent Learning, fought hard to bring KiVa to New Zealand. “We have such a lovely country, with appalling statistics. It is really grim”, she says. “The number of our kids that are hurting or not wanting to go to school breaks my heart.”

“It is pretty clear through research that most kids do not condone bullying,” Vercauteren continues. “They just get caught up in it.” It is at ages nine to 14 where bullying spikes in children. At this age children are spending a majority of their time at school. “This is not saying that schools are to blame,” says Vercauteren, “but this highlights the importance of a programme within schools that focuses on what bullying is, and how it can be prevented.”

But do New Zealand schools have the time or the resources to welcome a new programme with open arms? Vercauteren believes that the integration of KiVa will not be a problem, stating that the programme will fit perfectly into the existing curriculum and that it is not an add-on programme. What’s more, schools become part of the KiVa community, which is overseen by a KiVa support team. “It becomes a community”, Vercauteren says. “There are newsletters and KiVa days, where schools can discuss any issues they may be having with other people working with the programme.”

Of course, there have been numerous attempts to solve bullying in the past, and yet we still have poor statistics, so why is it believed KiVa will be the answer?

“The idea is to change attitudes,” Vercauteren says. She suggests that for some schools and parents there is a feeling that bullying is ‘a part of growing up’, ‘something everyone goes through’ and ‘something you will get over’. “But this idea leads to sinister stuff,” Vercauteren says.

KiVa also focuses on student safety but does so in a way that encourages engagement, Vercauteren says. There is an email function where students can contact members of the KiVa team, but in a way that allows some anonymity. Together with the email function there is an online game where children have their own avatars and learn in a fun way. “They can even dress them up,” she says, “and this is a huge reason for its success with children.”

Vanessa Green has worked closely alongside Vercauteren with KiVa, and she also believes that the programme is capable of reducing bullying in New Zealand, partially because of its perfect fit with New Zealand values of diversity and acceptance. “We have tried home-grown programmes, but we are a small country and we don’t have the resources. So my way of thinking is why create something new when we have got a programme that works?”

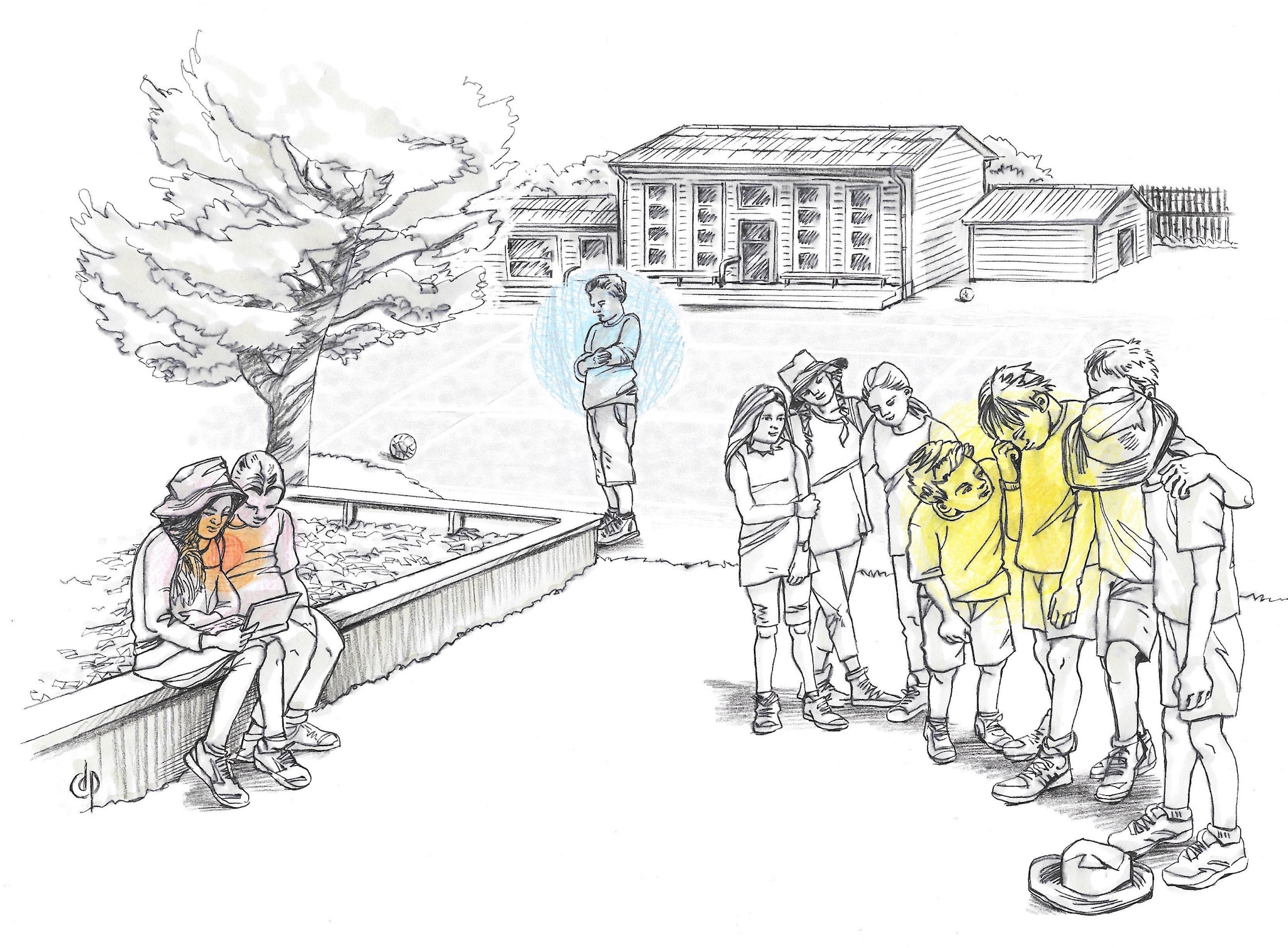

The pair both believe that KiVa’s focus on the whole school is a key reason for its success. “Programmes in the past have been well-meaning,” Green says, “but they have only approached certain aspects. Without seeing it as a whole-school problem, you will not be able to address the issue.” Green also attributes success to the programme’s attention to bystanders (the children who stand by and watch bullying happen). By taking away the bystanders, the bully loses power, she says.

“Children do not know what to do as the bystander,” Green says. “So KiVa teaches children what it means to be a bully, and that standing up and defending the victim is the new norm… Once kids know that other children and teachers have their back they will be more confident to stand up to bullying.”

KiVa may be a new programme to New Zealand, but it has already caught the eye of Marsden Primary in Karori. Celia McCarthy, the school’s director, acknowledges New Zealand’s bullying statistics and says that it is important that the school equips its students with the skills to stop these behaviours. “We need to teach our children to be responsible bystanders and to be good citizens,” she says. KiVa can help us do this, she asserts., because of the programme’s international results and the fact that it is backed by years of research.

“At the end of the day, bullying is not solely an issue for the bully and the bullied,” McCarthy says. “It is an issue for everyone in the community. That is why we believe in the value of this programme, which works with the whole school.”

The boisterous child goes to pick up another handful of bark. “Watch this!” he chuckles. The bully goes to throw the bark at the bullied child, when a bystander interrupts him.

“That’s not very nice,” he says. The other children standing around nod in agreement. The bully puts down his bark and gets back to his lunch.

The not-so-nice truth about bullying in New Zealand

According to the Bullying in New Zealand Schools report (2013):

- 68 percent of respondents indicated that bullying began between preschool (under-5s) and Year 4 (ages 7–8).

- Only 64 percent of respondents agreed that the strategy used in their school covered cyberbullying.

- 6 percent of respondents indicated they had received anti-bullying training or attended an anti-bullying workshop.

According to the TIMMS report (2012):

- The percentage of Year 5 students reporting recurrent bullying was significantly lower in 43 of the 50 countries in the study.

- Only one country reported statistically significantly more bullying than New Zealand among Year 5 students.

- 22 of the 41 countries compared had less bullying than New Zealand among Year 9 students.

- 14 percent of Year 9 students disagreed with the statement ‘I feel safe when I am at school’.

According to the University of Auckland’s Youth ’12 survey report:

- There has been no or little improvement in bullying at secondary school level over a decade.

- Youth (aged 15–24) suicide among New Zealand males is the highest, and among females the fifth highest, when compared with other OECD countries (2009 statistics).

- Among children aged 10–14, approximately one-sixth of all deaths are due to suicide. Most of these are Māori.

To find out more about how you can support your child and help reduce bullying, visit the following websites:

- KiVa — kivaprogram.net/nz

- Ministry of Education — minedu.govt.nz/Parents/AllAges/UsefulInformation/IsMyChildBeingBullied.aspx

- Cyberbullying — cyberbullying.org.nz