But before Atkins, back to Frank. As he observed, noir applied Hollywood’s narrative assembly line to an unflinching critique of the American mind, shot through with the Gothic existentialism of an immigrant European creative class. The result was an artistic creole of no fixed abode, a drifter pressed into service as needed — much like other 20th-century innovations such as jazz or pavlova.

And yet there’s an irreducible concreteness to the blackest of noir — and equally to its black brothers, sitting alongside Atkins’ effort in the ‘crime/mystery’ section of your preferred written-word purveyor. Like hip hop, whose gravity-defying flights of wordplay belie a persistent emphasis on realness, noir or hard-boiled fiction can’t just throw together a few leggy dames and hard-bitten gumshoes and call it a day. Trailblazer Dashiell Hammett did a stint cleaning the toilets while incarcerated at a Federal penitentiary. L.A. Confidential author James Ellroy, reigning king in the genre’s yellowing pages, secured his claim to realness as a peeping Tom, panty-thief and distributor of prohibited literature.

For a genre seen to thrive most verdantly in the shadows of New York, Chicago or Los Angeles, it’s easy to forget noir’s international pedigree. But do we not have darkness here too? Not to mention corruption, moral miasma and a long-standing drinking problem?

Sam Neill’s 1995 documentary Cinema of Unease makes a solid case for New Zealand’s long-standing tradition of black thought and art. Gaylene Preston’s Wellington-set debut Mr Wrong (1985) deployed sly feminism while Hollywood noir was still coasting on its own fumes. And Edmund Bohan applied noir’s standards of enquiry — of broken histories, buried secrets and archetypal vice — to the past of Wellington (and the country at large).

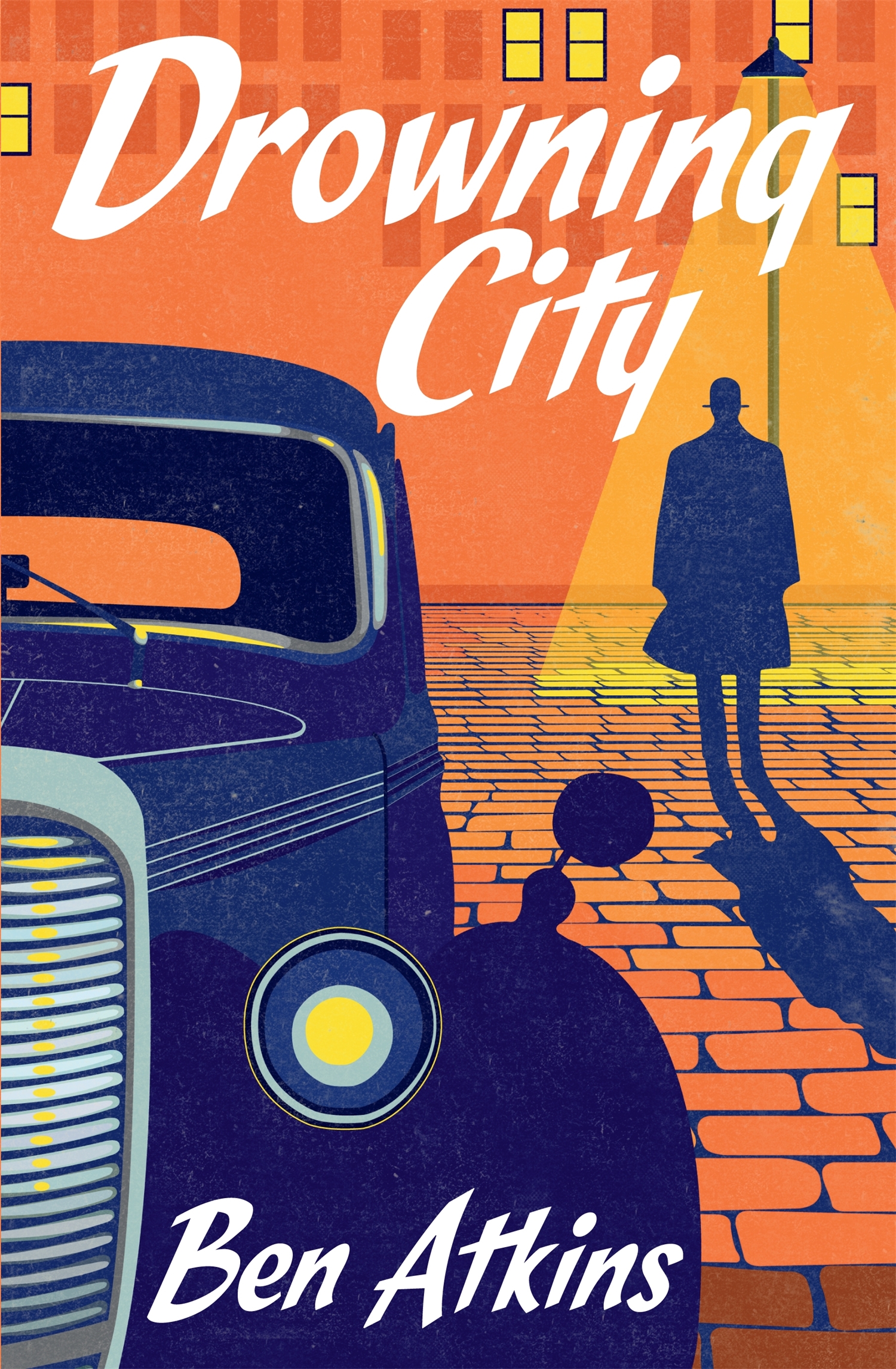

Atkins’ debut turns that dark glass further inward: to the tropes and truisms of noir itself. His novel takes place in a liminal city somewhere between Depression-era underworld USA and noir’s imagined spaces. This quintessentially 20th-century genre, fuelled by the dissolution of delineations — Europe and America, law and underworld, vice and virtue — has long had its back up against an unassailable bulwark, as if realness and artifice weren’t once more soluble. Now, authors like Atkins are making a brave effort at mapping even that shifting territory.