Maori was released in 1988, coattail riding the likes of Waititi favourite Shogun — and though the book’s European protagonist soon becomes embroiled in no end of ebony-hued mysticism, Maori’s Māori are far less alien than the novelist’s better-known xenomorphic foils. With the Māori Renaissance well underway at the time of publication, Foster’s work displays a prescient lack of elegiac condescension.

Back home, Graeme Lay has released the second instalment of his trilogy, James Cook’s New World. Picking up where The Secret Life of James Cook left off, New World trades in pioneering zest and a fastidious depth of research that Lay plainly delights in sharing. The figure of the Great White Discoverer has fallen in favour — return to America for a second and witness how nuanced the celebration of Columbus Day has become. So Lay’s wise decision, ably realised, is to present Cook as a thinker with a rich inner life, rather than the swaggering hotel namesake whose brusqueness would one day (spoiler!) prove so incompatible with the amorous trappings of St Valentine.

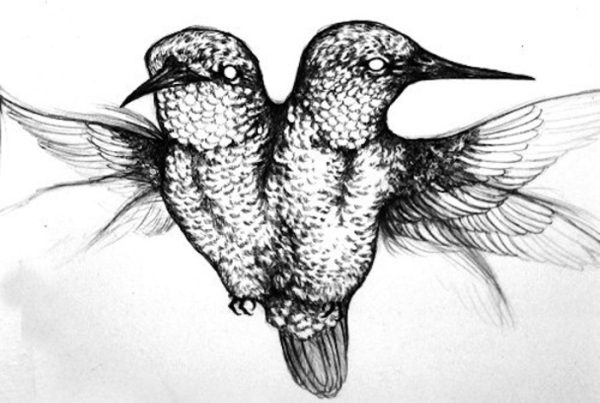

It’s the debut novel from Modern Letters alumnus Tina Makereti, though, whose perspective on formative Aotearoa warrants the deepest exploration. Where the Rēkohu Bone Sings builds on the author’s earlier short story collection, Once Upon a Time in Aotearoa, to create a work of cultural consciousness crossing boundaries of time, space and life itself. Makereti’s great skill is in dramatising cultural concerns extant since long before Cook — the story’s cross-generational narrative includes Māori, Pākekā and Moriori characters — with an unflinching intimacy.

And if unadventurous souls blanched at the zodiacal trappings of Ms Catton’s prize-winning opus, Makereti’s mythopoetical excursions into the numinous are a veritable taboo-smasher. Confidently voicing a metaphysics that resonates with the writings of Jung, Leary and indigenous cosmology alike, it’s an historical epic to dwarf any number of white-men-abroad fantasies; and in its way, as speculative a fiction as turned out by Stephenson or Foster. It’s a clarion call to further discovery — for author and readers alike.