Sit down, now, because what I’m about to say might come as a shock: this email was not really sent from the Canadian OSFI. It was, in fact, not even sent from Canada! Does anyone really fall for a scam like this?

According to figures released in June, New Zealanders lost more than $4 million over the past 12 months to scams. Netsafe New Zealand told me that it was $1.7 million in May of this year alone. There are some complex, long-game operations in play that demonstrably net results for the perpetrators. However, the example I give here is not one of them.

In his email, the scammer gives his name as David Geletey and he includes a contact phone number. I decided to ring it, just to see what would happen next.

In my day job I work as breakfast host at a local radio station, so I called ‘David’ from our studio and hit record, just in case he answered the phone, which I was certain he would never, never, ever, ever, ever do. But he did.

“Hello?” He sounds groggy. I imagine him rolling off a messed-up stretcher bed into a pile of cigarette butts, grappling with on old wiggly-chorded dial telephone and rubbing his face.

“Hi,” I say. “Is that David?”

Long pause as he blinks awake and kicks empty beer bottles to one side. “Oh yeah. Yeah, this is David.” What with the vague, slightly hungover laziness in his tone, this sounds official. I can almost smell his morning breath down the phone line. It’s worth noting here that David may well be Canadian but he speaks with a very strong West African accent, and the phone number I’m calling is a Pennsylvania one.

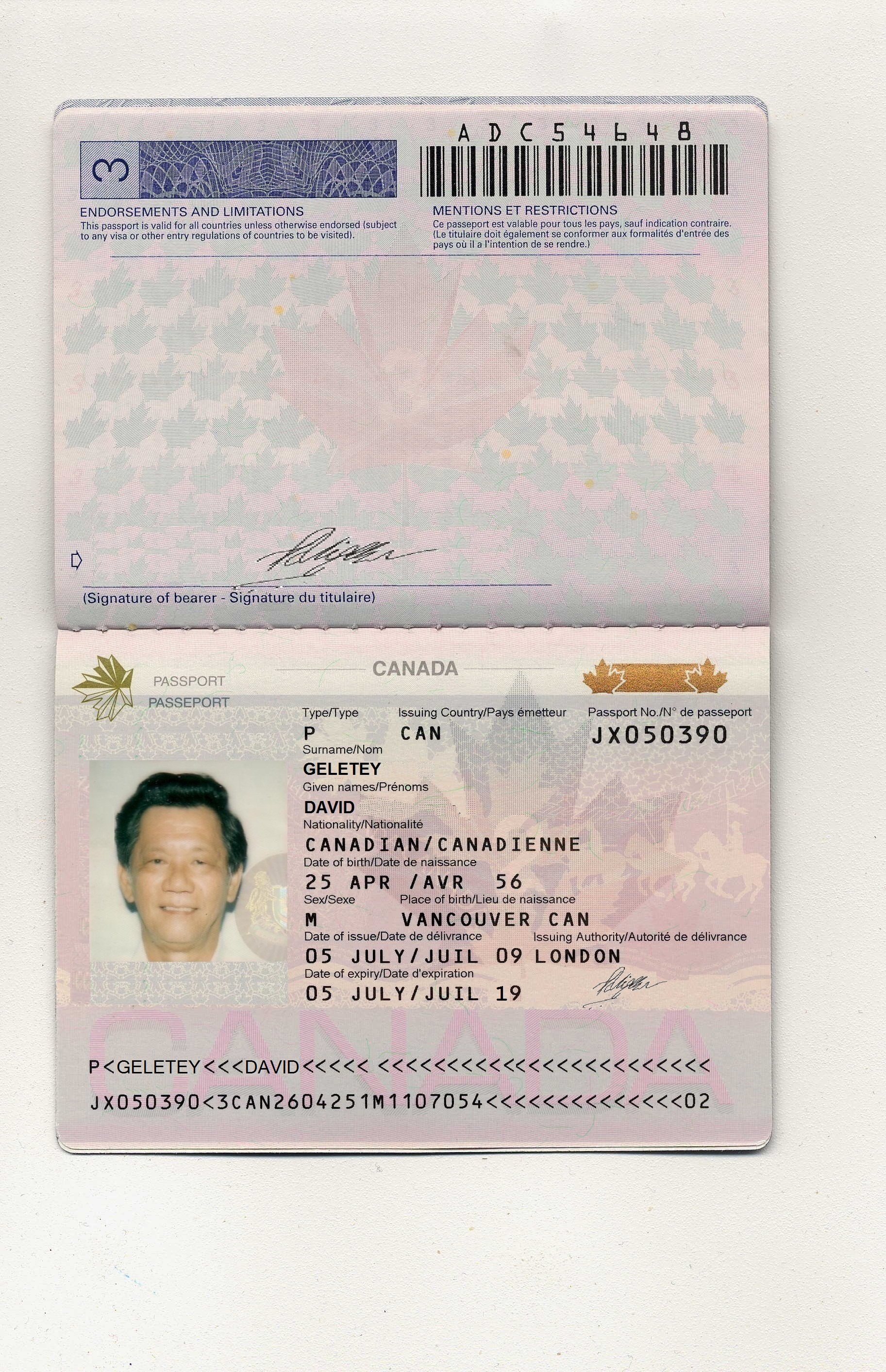

Long story short: David and I speak on the phone four times over four mornings and I record every call. By the third call he seems delighted to hear from me, and why wouldn’t he? I’m falling into his clever trap! Each time we progress things a little further until he emails me a not-very-legal-looking contract and a picture of what he says is his passport. At this point he tells me he will send details of a US-based lawyer who will make the money happen. That lawyer will need an advance payment. Ahhhhh… there it is.

In our fourth phone call I try this: “I don’t want to find out that this is a scam.”

“Wha?? Ohhhhh, Steve, Steve, Steve, Steve. No, no, no, no.” Fair enough. Repeating my name and the word ‘no’ over and over again has convinced me.

By now this has played out on the radio for nearly a week. In our fifth and final call I tell David the truth and I confront him, asking if he’ll admit the scam and tell me his real name. He doesn’t.

This particular scam is known as the ‘419’ after a clause in Nigerian law — there’s plenty about it online if you want to look. It’s been in operation in one form or another since the mid-1980s and the only reason it’s still done is this: sometimes it works. More importantly, there are other scams with an even bigger hit rate. In my week on air doing ‘Scam Watch’, a number of listeners called to tell me about friends who’d been fooled by duplicate Facebook pages, long-distance ‘love’ found on dating websites, official-looking letters from companies asking you to confirm security details, paying for packages that don’t exist and so on. There are hundreds of them.

Scammers are scum, but — unlike David — they’re not always dumb. Never give money to someone you haven’t met, never hand out a pin or password, and if you have doubts, call Netsafe or the Commerce Commission.