“Sometimes, I bond more strongly with art that I started off by hating,” says Leonard, newly installed as the City Gallery’s senior curator. Not everyone in the art world, or elsewhere for that matter, is so open to influence. But Leonard thrives on the grapple, the confrontation with the disliked object. He doesn’t mind starting off on the back foot. Take, for instance, the American artist Matthew Barney, whose highly experimental body of work spans sculpture, opera and filmmaking. “In many ways, his work is everything I thought I didn’t like: it’s theatrical, it’s pretentious, it’s silly. But I love it despite myself. It won me over. It defeated every criticism I threw at it.”

Leonard grew up in Auckland, came down to Wellington as an intern at the National Art Gallery on Buckle Street, and since then has worked in New Plymouth, Dunedin and Brisbane, where he was the director of the city’s Institute of Modern Art. That kind of contemporary arts space is where “a lot of the art world’s heavy lifting is done”, the real testing of edges and breaking of boundaries, the furthest advanced part of the avant-garde.

But the audiences in these spaces are, in Leonard’s own words, “tiny”. And so he started searching for a bigger canvas. “I came to work at City Gallery because I want to work somewhere with a real audience again, as well as potential for impact.” Curating, in this sense, is no rarefied activity; it is the construction of a bridge between producers and consumers, where the need to get those consumers, the public, across the bridge and into the gallery is as important as anything else. “You work with artists, but you also work with audiences. It’s party liaison.”

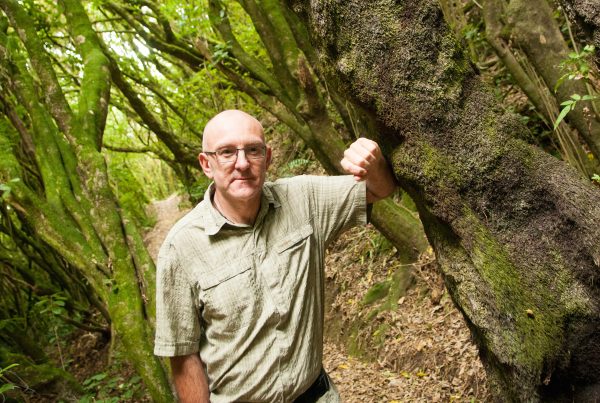

Leonard has come back with a desire to “curate up a storm”. But at the same time he’d like to shake the reputation he gained here as a young man in the 1980s, where some inspired curating — including a show that juxtaposed Colin McCahon with nationalist TV ads — gave him that dreaded label, an enfant terrible. “When I was in my 20s,” he says, “I used to get called an ‘enfant terrible’, but I’m 51 now, a senior citizen of the art world. I’m venerable. But, now I’m back in Wellington, I’m bumping into people who knew me back then and still think of me as an ‘enfant terrible’. It’s a mantle I want to shake off.”

Something he relishes as a curator is the freedom to move from genre to genre, from style to style. The art world has its dominant trends, of course; but how quickly that shifts. “As a curator, you can be all over something, then drop it and go in a completely different direction. Artists have to remain consistent, but curators can be fickle. The fickleness of the art world works for curators.” But don’t the artists, like jilted lovers, feel hurt? “Definitely, definitely.” But Leonard has worked with some artists for long stretches, others briefly; it’s the nature of the job.

In a way, it comes back to contrast — “all things counter, original, spare, strange”, as the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins put it. It works in art, and in life, too. Often our ideal lover is someone with sensibility that is different to our own but still meshes with it. “The last person you want to have a relationship with,” Leonard says, “is yourself.”